The following interview was edited only to remove non-words. The full context remains intact.

—

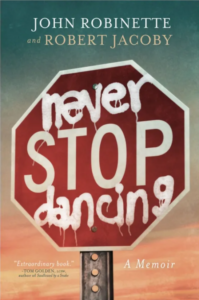

Lisa M. Blacker: I’m here today with coauthors and friends, Robert Jacoby and John Robinette. Never Stop Dancing: A Story of Grief, Male Friendship, and Healing Conversations is the title of their book, published by Inner Harbor House. Welcome, Robert and John. Your book was born out of friendship and compassion following a crisis. John, tell our audience a little about the crisis, and then Robert, if you will, tell us a little about the idea you had to help.

John Robinette: Sure Lisa. Thank you. I guess I’ll start the day it happened, April 29th, 2010. I was greeted at work by a police officer letting me know my wife had died suddenly in a traffic accident, a pedestrian traffic accident. We had two children, two boys, that were seven and four at the time. You can imagine how that just sent me into a place of grief, and confusion, and just wondering how to get on with life.

Watch and listen to the full interview, here. Continue reading the transcript, following the video.

.

[Interview, continued]

LMB: The friendship that the two of you have is one of the main reasons that you were able to accomplish this. I wonder if you can tell us a little bit about how you developed such a friendship that seems to be so uncommon, especially for heterosexual males, or for males who are platonic friends.

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

LMB: Can you talk about that?

JR: I’ve known Robert as long as my older son’s been alive, I literally met him when he was a week old. The company I was working for was partnering with the company Robert worked for on project. We met during the early proposal part of that. That’s how we first met, it was really around the workplace. We got won that work and I wound up spending a fair amount of my time on the job site with Robert. Our offices were right down the hall from each other. We bumped into each other regularly, we just started a conversation around music, and it went from there. We’d get together for lunches, and pretty quickly I think we were able to identify areas of common interest around a wide range of topic, but it came back to, I think, we shared experiences as being in marriages, being parents, and it was those conversation I think where we truly connected.

RJ: Both of us had a real keen interest in discovery, finding out what other people though I think this, I would agree with John, this just went back to the first few times we met where we were asking questions beyond the workplace, about what you did in your personal life, did you attend church, what was the marriage like, what were your other friendships like? And then we quickly explored areas of common interest, and that included politics, history, religion, philosophy, current events. I mean really on from an early start, nothing was really off-limits for either one of us, and I would add to that that in our conversations we both held each other in regard and esteem so that we felt comfortable and free to explore pretty much any topic we’d want to explore. I think that formed the basis for my ability to ask him as a friend 15 years later, 10 years later, “Would you sit with me in this conversation?”

JR: Robert and I come from different perspectives on the world, and if you didn’t know we were already friends, and you just looked at who we were as individuals, you would probably not guess we would be friends. I think that our ability, as Robert was saying, hold each other in regard, and also hold onto our individual world views as valid, and be able to challenge the other person, or have difficult conversations but with respect and dignity. We’re not trying to make the other person wrong. [crosstalk 00:05:04]

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: Which I think happens a lot in our discourse these days. Somehow that friendship developed in a way that allowed us to reveal that full self in a way that I don’t think is… It’s really hard to do these days.

***

LMB: Now, I know because I’ve read enough about the two of you that your backgrounds are… not that they’re so different, but you have differences certainly. It isn’t as though you agree on everything. Why do you think the two of you… Robert, this one will be for you since John just gave us some of his perspective, why do you think the two of you were able to develop such a solid friendship even though you have many differences?

RJ: John’s a bright individual, and I’m attracted to that. I’m attracted to bright people. By bright, I don’t mean just intellect, it’s more than that, emotional capacity, capacity for live, capacity for love and living. I sensed that immediately. I would almost call it in the spiritual realm of things, a spiritual sense of things. I wasn’t afraid to reach out to him. I wasn’t afraid to share things with him that most people I think at the beginning of a friendship might not share.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: I felt a comfort with him that was evident pretty soon after we met, and that builds. When you can build on a foundation like that, it makes it stronger and stronger I think going forward, and there’s a dependence and a reliance on the person. I mean, John and I, it’s not like we’re on the phone or seeing each other every other week. We have about almost an hour apart, but when we get together, it could have been two months, three months, four months since we last saw each other, and we just pick right back up.

***

LMB: What can other men learn from reading your book about friendship and compassion?

JR: That’s a really good question. For me, we as men, even in our enlightened days, as we tend to think they’re enlightened now, we’re still taught at least implicitly to some of those classic male, masculine attributes around strength and protection. Those are valid and necessary, and can also get in the way of being open and vulnerable, especially with another man. I don’t know if there’s a secret or not, but there’s something I think courageous and brave in being vulnerable. It’s not like I say, “I’m going to be courageous and brave and be vulnerable today.” It doesn’t really work that way, for me at least.

JR: I don’t know if it was my background, my parents, or what, or the DNA. I’m 54 years old now, so I’m not sure this has been always true, but at this point in my life, when Robert and I met, which was 18 years ago, even then I think that we somehow let out clues to each other that we had had some life experiences that weren’t fun, and rather than focus on politics and religion where people tend to shut down, we were able to see past that, and see that we’re connected through the broad experience of human life, and suffering that comes with that.

JR: That sounds big and fancy I think hearing myself say it, but I think that’s what attracted me to Robert was he was able to share what was going on in his life at the time. Fairly quickly it was like, “Okay, this is a deep thinker,” as Robert was complimenting me, I appreciate that. Robert is also a deep thinker, extremely well-read, maybe the most well-read person I know of personally. I don’t know, I don’t have this same friendship with all men. I think there was something in the way we were able to connect, but I think we both came to the table like this, just being able to open up just enough. It wasn’t like we were just jumping into our own personal 12-step program right away. It wasn’t like that.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: But there was just enough of, “Oh, tell me about your kids,” or, “Are you married, or what’s going on? Oh, I see. Life’s a little more complicated than it looks like on the outside.” You know? Things like that.

LMB: Robert?

RJ: For me, I’ll start out with the caveat like John did that this is for me personally. I’m a poet and a novelist, so by those definitions alone and by what I do, I tend to think more, grapple with life, question more than your average bear, and it’s taken me some time to understand that and feel comfortable enough in my own skin to own that. It was about that time when I was meeting John, soon after that going through my own divorce, and it was almost like a rebirth for me to come into my own. And really to shed previous thinking, previous modes of being, if I want to call it that. It sounds like a cliché, but embrace who you are and to feel comfortable in your own skin, and that’s okay. For me it was nothing more complicated than that. Meeting John was fortuitous maybe in that timing that maybe he came into my life at the time that I needed to have a good friend like that. [crosstalk 00:10:37]

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Go ahead, John.

JR: Not all my male friendships are like… I do have other close male friendships, I just wanted to be clear.

LMB: Okay.

JR: I have other close male friends who might be watching this thing.

LMB: Good point, sure, that’s fair.

JR: My friendship with Robert is distinct in its own merit, you know what I’m saying? So I could count two or three other men with whom I have close relationships that are distinct on their own merit.

LMB: Okay.

JR: You know what I’m saying?

LMB: Yeah.

JR: But not all my male friendships have that same… I just can’t, I don’t think. You know?

LMB: Let’s continue with that then, because what I want to know is what are some of the elements those friendships have in common with the friendship that you have with Robert. Is it about the vulnerability and the trust? What do you think are the commonalities?

JR: There is a level of trust. I think oftentimes in male friendships there is an undercurrent, maybe a competitiveness, an undercurrent.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: Even if it’s not stated. But I don’t feel that. Sometimes I do, but it’s not a prevailing emotional undercurrent with those relationships. They’re free to be sort of how they are. I think these friendships are ones that came to me, not at the exact same time in my life, but in my… you know, I had already become an adult. I have some close friends from my youth, but those are different too. I think I was able to make these friendships or be a partner in those friendships from a different adult stance, if you will, as a man having, I went through a divorce in my 20s, getting married again, just whatever lumps, bruises, and scars we accumulate as we grow.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: Enough of that had happened that I didn’t feel like I had to be somebody I wasn’t necessarily.

LMB: So authenticity is a factor as well.

JR: I think so, I think so, to the extent that we know who we are.

LMB: Yeah.

JR: Like any of us.

***

LMB: Robert, what do you think about male friendships that you have? What are the commonalities comparing to the friendship that you have with John?

RJ: I have another close friend, but I have to say that what I went through with John, if we didn’t have the book and that experience, I don’t know if our friendship would be what I consider extraordinary, or super unique. I think what I went through with him during that year, I mean he laid his soul bare to me, and there are some things that just aren’t in the book.

LMB: Yeah.

RJ: As raw as some of the passages are, we did have to turn off the tape recorder and just cry together. It was awful. Having said that, I can truthfully say I haven’t gone through something with another man, like that episode, like I have with John.

JR: No.

RJ: At the same time, I will say I shared a deep friendship with another man that was more on an intellectual, philosophical level, but we enjoyed our company, and I would springboard off what John had touched on. I think to me it’s more of a bond, it’s not competition.

JR: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: [crosstalk 00:14:02] I would say is the commonality. It’s a bonding experience, it’s not a competition.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: That’s not only refreshing, but very much needed for me. My soul needs that. I need that bond, I need that companionship, that friendship.

***

LMB: Each of you is a father. How does this experience with, as you pointed out, Robert, the interview process over the year with John, having that strengthen, deepen your friendship? How has that experience affected each of you as a father? I’m wondering specifically with regard to nurturing boys. Has that affected how you parent at least with regard to helping the boys to develop male friendships?

JR: There’s a sensitivity to it, and also I’m trying to contrast… I can answer that question I think two different ways. One about what was going on 10 years ago in the middle of our conversation, and how that influenced me as a father, versus today, which is different now. This is in the book. It sounds cliché, it’s in the book too, is how to be present in the moment, and how to… When someone comes to me, one of my sons in particular, but anyone really, is how do I stop what I’m doing, how do I stop the conversation in my head so that I can be 100% into this new conversation? With children, they’re just coming at you in the middle of an email or whatever, so we’ll like, “Yeah, mm-hmm (affirmative). Okay, yeah, I’ll get to that.”

JR: As a response, that’s more of a dismissal than an actual conversation or one of engagement. That distinction became clear to me that life was happening around me, and I needed to pay attention to it, specifically the life of my two children. It’s not to say all of a sudden I was instantly this very focused, engaged father with them. It wasn’t. It’s not like it changed me per se, but I now had a new awareness of when I was not engaged with them. It still happens today. It’s not like I taught them, “Hey, be engaged in your conversation.” But I try to model here’s what it means to listen to somebody.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: I don’t think that’s just for men, for boys. I mean, that’s just as a human being in conversation. Today, I would… They’re older now, one’s graduated from high school, one’s in high school, so how I am with them now is different, so how to be authentic with them and not hold back is an ongoing project with them. They’re different people, and how I can be in conversation with them is also different. You know what I’m saying? So just understanding them as individuals, not just my boys, and that they each hear things from me differently based on their age, based on just their personality types, is sort of an emergent awareness for me. I’m not sure that’s a good answer, but…

LMB: What I’m hearing is in your interaction with your sons, you’ve been practicing awareness and modeling the behavior rather than just having them be in the background reacting. You are making a conscious decision to be present with them, and in doing so, you’re modeling what is a healthier behavior for them to have with their interactions with others. I can see how that in your parenting can help them to say, “Oh, this is how my father treated me,” and even on a subconscious level, “I’m going to treat others this way.” Is there anything you did in a more forward manner teaching them about male friendships such as you have with Robert?

JR: This isn’t a very good answer, I don’t think, to your question. I wish I could give you here’s the seven tips for having that good male friendship. But I think it’s just being, “Hey boys, I’m heading out, I’m meeting up with my good friend Robert. We’re going have dinner or whatever.” Just let them know that that’s part of my life.

LMB: Yeah.

JR: You know what I’m saying? Or have friends come over. The church I’m a member of for example, we have a men’s group where we meet once a month.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: It’s pretty informal, there’s hardly any structure to it, and I’ll host it here at our house, I don’t know, once or twice a year maybe.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: They’d see that. I just make it part of my life, and I don’t try to make a big deal about it necessarily. Teenagers, they’re more interested in their peer group and how to separate from their parents anyway, so at this point, I have to let actions speak mostly. Because I know the words will be rebuffed.

LMB: Okay, thank you. Robert, I want to ask you the same set of questions. How have you taught your son about male friendships, and has your relationship with John influenced any of the discussions related in the last couple of years?

RJ: Well, this is interesting because the events in the book take place 10 years ago now-

LMB: Oh, right.

RJ: … where I was 10 years ago, and we just published the book recently last year.

LMB: Yeah, that’s what threw me.

RJ: It took that long to get through that process of just living through that year, doing the interviews, cleaning up the text, revision, publishing, et cetera, et cetera. But I had to tell you that to tell you this, that who I was 10 years ago… To answer your first question I think, I was greatly impacted, obviously, from being with John that year. I think that having the visceralness of that experience I couldn’t help but be affected and impacted by that. I interviewed him eight times over that year. Every time I came back, sometimes I would just go out to my car… John and I would speak, we would do interviewing for 30 minutes, 1 hour, sometimes up to 2 hours. Almost every single time, Lisa, I would come back, sit in my car, and just weep, just burst into tears. It was so draining being with him and talking about these things.

RJ: I would come home, my kids were teenagers, one was already out, my son was out of the house I think at that point. It’s a cliché to say it, but I had a new appreciation, a new discovery for who my children were, and the preciousness of life, and the immediacy of life. I think similar to John’s experience, I didn’t have a seven-step program, this is how you live or this is what you should do. Fast forward to today, 10 years later, my children are all adults and we’re on that adult-to-adult, certainly parent-child, but it’s an adult relationship.

LMB: Yeah.

RJ: Each one of my three children, I have one son and two daughters, is unique and special in its own right. We are who we are, and we’re on that playing field of adulthood.

***

LMB: Robert, tell us more about fatherhood, your relationship with your father, if you’d like to share that, and your relationship with your children.

RJ: Sure. You don’t have to dig too far into psychology or psychoanalysis to understand that men are imprinted from their fathers. They see their fathers as a model, whatever that model might be, good, bad, or indifferent. My father was from the World War II generation, he actually served three years in the Pacific. He brought whatever experiences he had there, and I didn’t hear very many of them at all, he brought those experiences back with him to live his life out fully. He was only 18 or 19 when he went into serve. I learned from him, I suppose they would call it the model way of learning, or him teaching me what it is to be a man, what it is to be a father, again, good, bad, or indifferent. Were certain pieces missing? Some people might say that. He loved us in the way he was able to express it. Was it a full expression? That’s arguable. He might say that he did his job or he did his duty.

RJ: For me and my relationship with my children, I can look back certainly when they were being raised when they were children, and I didn’t feel present. John talked about that in the book too. He thought he was present, he felt he was being present and being a good father, but when this catastrophic event happened and Amy was killed, and he had to immediately become a single parent, a single father, that was his realization that, “Oh, oh wait. What I thought was true was not true.” I think as we get older, we can look back [inaudible 00:23:46] you don’t want to do too much [inaudible 00:23:47], I certainly don’t, but I can be as present as I can be today, as confident as I can be today as a parent, as a father, as an older father, I’m a grandfather now-

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: … I have two grandchildren. That my capacity for love has grown over the years, I don’t know if it’s that as you get older you get the edges buffed off of you by life.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: You get kicked in the head a few times, and you get those sharp edges honed down, roughed down a bit I think. This is my experience.

LMB: Yeah.

RJ: Again, it’s going back to that modeling experience I think where I’m present with my children, my grandchildren. I enjoy them for who they are as individuals, and that to me is love, being present.

LMB: Beautiful. Beautiful.

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

***

LMB: John, if you’re willing to talk about your experience in suddenly becoming a widower, and a single father, if you could talk about the grief and the life changes. Specifically, at least part of it, what advice would you have for a man in a situation where he’s suddenly a single parent and the grief that takes place there?

JR: Right. I guess I would preface what I’m going to say is that the events that can trigger grief can be broad and wide. You don’t have to lose a spouse to experience grief. Losing a pet can create grief, losing a job.

LMB: Living through COVID.

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: Living through COVID, illness, losing a parent. I think for men it’s complicated to understand what am I supposed to do. I think our culture puts some expectations on all of us on how we ought to grieve, we’ll even talk about the stages of grief sometimes, which I think is a simplistic understanding of the complex range of human emotions are not linear. They come back, they circle back, we go through the same anger, resentment, shock, over and over again. I can say now 10 years after, realizing that my grief process has continued to this day, and has evolved with the years as the years have unfolded, and as I get reminded of it through the life changes of my children. There’s a graduation and the mom’s not there, right?

LMB: Yeah.

JR: It’s not as crippling as it was say 10 years ago, but it’s still there nonetheless. I think for men, and this sounds sort of perverse, but the advantage I had at age 42 when my wife died was that I had gone through a loss, I had to grieve a marriage in my late 20s. However that happened, I was in contact with therapists, with other men, the men’s group, just the coincidence of relationships I had, so I knew the importance through the essential need for me to seek professional care, a therapist, and that there were other people who could support me. I did not hesitate when Amy died to almost immediately reach out for help, it just felt natural and because I knew it worked, it worked for me. So the self-care piece of this for men I think is one that’s not well talked about or sanctioned in our culture. There’s sort of this sense of men and stoicism, and pulling yourself up from the bootstraps that’s sort of baked into our whole mythology, especially as Americans, right?

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: There’s wisdom to that, and that’s appropriate at times, but I think when, for me in particular, going through the tremendous grief, I knew I had to surround myself with people who could help me. Not just friends, but therapists, acupuncture. I craved human touch so much that getting a massage, just a therapeutic massage, did wonders just for that one hour, just to escape into the relaxation of that. It doesn’t have to be complicated. All those things add up over time that I was able to construct for myself a fairly significant support structure. I had my church, my church rushed to my support too. That I was in a community faith helped with my survival, especially in those early days. Some of it was just the luck of being in the neighborhood I live in, it’s a pretty close, tight-knit group.

JR: I know not everybody has that, and that makes it, I think for some people who are not connected to their neighborhood, or they’re new to their neighborhood, or maybe they don’t have a faith community. It doesn’t have to be a faith community, but some community of connection that can provide just the meals, and doing laundry, and just the simple tasks of life, especially if you need to care for other people. We talk in the book, I think, putting on the oxygen mask, which alludes to if you’ve been on an airplane, and they will give you the speech in the event of a sudden loss of cabin pressure, the oxygen mask will come. If you’re traveling with a young person or someone who needs your assistance, put the oxygen mask on yourself first before helping them. That’s because in cabin depressurization you’ve got about 20 seconds or you’re going to lose consciousness.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: If you lose consciousness and someone’s depending on you, then you’re both in trouble, right? You have to take care of yourself first. I think men in particular, that’s not really part of our bringing up, our upbringing I should say, is to know how to take care of ourselves.

***

LMB: We talked a little bit earlier about how fathers can teach their sons about male friendships, and you were talking about just demonstrating the behaviors and modeling the behaviors. It occurs to me that the way you express yourself in grief also is a way to model that for the children, to be honest about your emotions. There’s so much in our culture, in the United States anyway, about men and emotions; men are only allowed to be angry or to be strong businessmen, and thankfully a lot of that is changing. What has been your experience in expressing grief in front of other men who are perhaps more old fashioned and have older standards as far as how men are allowed to emote?

JR: I’m actually not sure how to answer that question. I guess the example that popped into my mind as you were saying that is my own father. I don’t really know if it’s valuable to go into too much detail, but I just know that it was hard for him to know what to do. His instinct as a father to help his son who’s in turmoil was clear, he wanted to help, but he seemed at a complete loss as to how to actually do that beyond the mechanics of arranging things, you know?

LMB: Yeah.

JR: With that one exception, I don’t know. Maybe there was a self-selection process underway already where I didn’t really have people like that around me, or if I did express my deep grief emotions in front of a man who was uncomfortable it, they self-selected out too. I don’t know if I have good data to be able to report.

LMB: Okay. Yeah, that’s fair.

JR: What I did find, actually, was that, not just men, but there were men who when they saw how, I guess, expressive I had been, they would then share with me deeply held secrets, and fears, and traumas that they had experienced that they hadn’t shared with many people. The loss of a child, an infidelity, a father that was abusive, the alcoholism. I think this is in the book too in the epilogue, just the range of human suffering was very clear to me in those early months as other people shared their own… when I say loss, I don’t necessarily mean death, but their own loss of innocence, their own loss of love, whatever it was. I think the message is it’s everywhere, and you really don’t have to look that far to find it. If we just gave ourselves permission to set aside the fear, which I think a lot of the anger you mentioned, it’s okay to be angry, I think that’s masking an underlying fear of something.

LMB: Yes.

JR: So the anger is a self-protection mechanism. Really if we could dig past that into the fear, then we actually become stronger, there’s actual courage that then is able to buffer us from the next set of inconvenient abuses, natural disasters, human grievances against each other.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: It’s endless. It’s going to be endless.

***

LMB: Good point. Robert, you had a lot of compassion to reach out to John while he was grieving. Did you have experience with grief that made it a little bit easier for you, or at least so that you knew that this was going to be a helpful experience? What’s your experience with grief?

RJ: Yes, well, I touch on this in the book, so I can talk about it here with you, Lisa and John. I’m a suicide survivor. I think for me fundamentally the acceptance or rejection of your own life and your own self is the prime grief generator, if you will. Are you going to embrace life or are you going to reject life? So that is part of my background. My struggles off and on earlier in my life with depression, I talk about it in the book a little bit too, that also has certainly flavored my world view, colored my world view. Having that in me as a person, as a man, approaching John with this idea I thought and I felt at the time that this would be helpful to him. I saw him in his grief, I saw him struggling. Really I thought, “What can I do to help? How can I help him?” [inaudible 00:35:38] Come to him just with who you are. You’re his friend, talk to him. You have deep, wide-ranging conversations with him, so do that. Be who you are. So that’s what I did. Thankfully John said yes, and we started our conversation, and that’s what led to the book.

LMB: The reviews have been beautiful, moving. It seems like you have reached people in ways that I imagine you had hoped. If I could have from each of you briefly, who do you think is the reader who will get something out of this?

RJ: Because I had the idea for this book, I immediately thought, Lisa, that anyone who is interested in life would be interested in this book.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: I don’t mean that lightly. I don’t mean that on the surface. I mean anyone who wants to grapple with life issues, what it means to be alive, what it means to love, what it means to reason through life, and what it means to connect with community, what it means to wrestle with God. There are so many things, I should say themes, that John and I both wrestle in this book. This is a book certainly about John’s experience through that year.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: But also, it’s a book about me as John’s friend with him during that year.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: I think in that unique way it’s a book about both of us and how we were both transformed through these events during that year.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: I think that’s what’s reaching people. That’s what’s touching people. I’ve read a good number of the reviews, and I think that is how people react to this. Yes the book, that’s a devastating event John went through, there are raw emotions certainly, especially in the first 40 or 50 pages. But coming out of that, there’s a way to live, and that’s what I wanted to capture in the moment with John in my interviewing him. How do you get through this? Not just that atomic bomb event, but how do you recuperate, how do you recover, how do you go on living?

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: I wanted to capture that, and I think that’s what people are reacting to so positively.

***

LMB: John, I know, my understanding anyway, is that you weren’t focused on the book, but in the interview process and all of that of course, was there a point where you felt like, “Oh, yeah. This as a book is going to help this group of people.” Is there a group of people you felt would benefit from reading this book?

JR: Yeah, it’s interesting. At some point, I think… I mean, Robert and I were clear that was going to be something published. What its final form was going to be in the moment, I don’t know that we could have imagined, or I couldn’t at least.

LMB: Yeah.

JR: I think I did have a similar sense of the universality of the life experience, which includes death, that many people could benefit from it. I think now with the benefit of time, and actually seeing some of the reviews, and hearing from people who have read it, I think what might be distinctive is an articulation of one person’s experience, my experience, that the way Robert was able to pose questions in the way he allowed me to be as vulnerable as I’ve probably ever been in my life. There is an expression of that grief that is, I’m going to say, raw, poignant, I want to accurate, it doesn’t seem like the right word. But what I’ve heard from other people, a friend of mine lost an adult child in a car accident recently, right as the book was coming out, so she had read the book as her grief was unfolding, and she remarked to me a few times, “I didn’t know what was going to happen next. I read your book, and it’s just like, ‘Oh. That explains, for me, what was going on.'” It just touched me deeply that she was able to find maybe some comfort, and that what she was feeling or experiencing was her unique experience and also normal. You know?

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: I’ve heard from a few other people that it provides an insight, for those who are nearby someone grieving, a different way of understanding what… It’s like, “Now I know what Uncle Joe is going through when Aunt Suzie died. Now I understand that differently.” To me, that’s just been a remarkable gift back to have just even those kinds of comments. It fills me up with, joy’s not even the right word. I don’t want to be happy about that, I guess it’s a privilege maybe to have been able to hear those messages.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: Yeah.

LMB: Perhaps for people like your father who didn’t know how to comfort you through the experience.

JR: Yeah, perhaps. Mm-hmm (affirmative).

***

LMB: Do the two of you have any plans for any kind of follow up project together?

JR: We do.

RJ: We do. Yeah, John can talk to it, I’ll follow on.

JR: Right, so we have our individual pursuits in life, writing and other things, but with respect to Never Stop Dancing, we’re imagining a follow on, sort of a companion book, that would be sort of a daily meditation.

LMB: Yeah.

JR: We’ve begun going through the book and pulling small passages or quotable areas that would be one per day, but then maybe a brief reflection from one or both of us on that passage for that day. You probably picked up we’re both fairly interested in other wisdom in the world, whether it be from scripture, or philosophy, or history, or even current events, interweave with our own words that would be the daily meditation, maybe those from some others that would sort of round out that experience. But we would reflect on it within the broader themes that are in the book.

LMB: Great.

JR: That’s a work in progress.

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

LMB: Excellent.

RJ: Yeah just to add to that, because there are so many themes interwoven through the book, this next one I think, that John and I have talked about, would give us both a bit more freedom to explore those themes, whether it’s the theme of community, or love, or God, or spirituality, or psychology, rituals and traditions.

LMB: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

RJ: Never Stop Dancing was born of a moment, I think we’ve both talked through that our next effort together would be born of love, and hope, and future, forward-looking, and living, and being alive.

LMB: Wonderful.

RJ: I’ve got two novels. I’ve got a novel I’m working on right now, so we’re hoping to get to this next project together.

***

LMB: Excellent. Never Stop Dancing is the title of the book. What’s the website? Is it the same?

LMB: Robert, what will our audience find when they go to that website?

RJ: The book website is fairly content-rich. We have a Q&A session with the two of us, me and John. We have a link to our other media appearances, articles we’ve written, interviews we’ve done. We were on some TV shows, people can see video clips of that. There’s also a one-pager for book clubs.

LMB: Oh yeah.

RJ: It’s a good handful of questions to prompt people for questions if they want to read the book during a group discussion. I would say though several reviewers on Amazon.com pointed out that they want to learn more and they want to hear more, and they’ve noted that would be a good book for a group discussion. We agree, and that’s why we posted the book club discussion questions online.

LMB: Excellent.

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

***

LMB: Gentlemen, thank you very much for spending your morning with me recording this. The Goodmen Project thanks you for talking about vulnerability, and men’s emotions especially. Thank you very much.

RJ: Sure.

LMB: Best wishes to you.

RJ: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

JR: Thank you, Lisa.

RJ: Thank you, thank you, Lisa.

LMB: Okay, bye-bye.

—

This content is sponsored by Robert Jacoby.

This post is republished on Medium.

—

Credits:

Video editing by Jackie Graves.

Transcription by Rev.com

Photo courtesy of the co-authors’ media kit, modified